If I had my wits about me, I might have questioned the look of the horse. It was my horse, but not my horse—as familiar to me as the sky is familiar, a natural constant, perhaps he was part of my own legs, red as the leather of my belt. But as I considered it, the longer I felt the movements beneath me, the less sure I became that it was indeed my own horse and I was jolted alert by a fear that I had stolen him in the dark by mistake.

It was a cold spring dawn. My breath misted before me in those startled bursts, lit gold in the meagre sunlight broken through trees. I released the pressure on my side and contemplated my misfortune, to see my hand coated in my own fresh blood and steaming that same gold, and I was quick to replace it, two fingers tucked under the gash through the layers of maille and linen, to press firm. It was the only warm part of me. My other arm was too heavy to do much more than grip the reins, struggling to bear the weight of my shield. The blow to my helm had surely jostled my brains, my vision swam in rhythm with the throbbing pain of my hand pressing against the flow of blood. What distance I had ridden through the night, there was no way of knowing, the landscape was too new to me.

I hadn’t fled—I knew I hadn’t, though I had no reason for knowing. The horse was taking me without encouragement down a country path, farms to one side and forest on the other. By mid-morning I was forward in the saddle and I cared not where the horse took me.

“You look half-dead as a sorry thing,” Brice said. I hadn’t noticed him. He walked alongside the horse (which I decided must be my horse for it trotted so mindfully of me) with his hand on the bridle guiding the beast, as I couldn’t. Brice’s eyes were blythe, he seemed ready to laugh at me as if I had made some jest. He wore no helm nor coif and bore no arms, his hair sticky and matted with blood and mud, and his surcoat might as well have been dyed with the same, so hidden were his colours. He looked hale despite the mess of him and so I had to assume wherever we had been had harmed him none. “Have you been tended to?” he asked with a tilt of his head.

“No.” The word came out of me like a croak. In truth I couldn’t remember, but since I bled so richly I doubted I had.

There were swift footfalls on the path just behind us, Brice turned to look, but I could not. “Why didn’t you mind yourself, then? You think yourself immortal? Don’t think I’ll be catching your fool arse when you fall.” Dand had jogged to catch us, easing his pace at Brice’s side but he spoke as if he could have ran a hundred miles and it would have troubled him not. He was dressed as I had last seen him, a woolen tunic of faded woad-blue, and a hood the colour of rust pulled down at his back. His hair was clean and long, ale-brown, his face freckled thick like the sun of midsummer slapped him. It was then my breath caught hard in my throat, my blood seemed to heat through my fingers. I hadn’t seen Dand in months, and miles away. He wore the belt I gave him when we parted. “Should we get him cleaned up?”

“Come on, I hear water.” Brice led the horse on, finding a deer path through the wood. A man sat alert on a tangle of roots beneath a yew tree, looking down into the gurgling little beck not far from his feet. Grey of hair and beard, dressed like Brice and myself, his helm resting beside. I recognized him as he turned, though he didn’t regard me with much warmth. That was his way, though, surly old William, and even if I had an inkling to take it personally I had little energy to act on it. Truth told I was relieved to see him, my shield-arm felt lighter.

Dand laughed. “We’ve stumbled across a vagrant, here!”

“I’ve been waiting for you all. Heard you might come this way.” William stood from the knot with a chime of maille.

Dand had never known William or Brice, yet they were greeting each other as if they were all well met acquaintances, gripping hands and nodding heads and laughing. Before I could question, Brice and William were helping me from the saddle and I was shouting at the tearing pain in my side, and the earth swayed at the pressure of my feet. I fell to my knees, with Brice’s hand at my back, and I retched blood and bile. William clucked at the sight of me, and I could see myself in the reflection of his helm still rested where he had sat, a distortion of red and brown and iron-grey. Brice and William got me upright and started at the ties of my armour, while Dand went to the water’s edge.

Brice stopped. “I can’t touch your shield.”

So with bloodied fingers shaking I pulled the straps free and neither William nor Brice caught the wood as it fell with a thud to the earth. I had no thoughts left but for pain and let the shield lay where it landed, rocking like a shallow cradle. Once they removed my maille and stripped me down to nothing but braies, the extent of the damage was clear to them, but I couldn’t dare look down at myself, instead my eyes were up at the yew needles above me in my determination to stay awake.

I could hear William’s breathing near my head as they laid me amongst the knots of roots near the water’s edge. He held my head between his calloused hands and turned me, examining the dent I was sure must be there. But he said nothing, only balled up my clothes to place under my head and went to where Brice knelt, and joined him in a good scowl at me.

“What have you gone and done to yourself, Allain?” Brice asked, his eyes shining, though from suppressed mirth or tears I couldn’t tell.

“I got myself stabbed in the gut.”

“Aye, that you surely did.” Brice spoke to me through their work, he and William cleaned me, the water so cold and I hissed my shock at the pain of it. “Do you remember the battle?”

“No. Not much. I remember getting hit in the head.” I swallowed dry. “Who’s horse is that?”

“It’s your horse,” Dand answered as he fetched water for me to drink. “You must’ve been clubbed right fearsome, I’m surprised you can see at all when you ask questions like that. ‘Who’s horse.’ Remember when you took Elspet for a ride and her father caught you? He was roaring mad! And doubly so because he couldn’t catch you with his slow little nag, you pair of fools tore through the flax for your little tryst.”

I did remember, and the dried blood on my cheek cracked at my smile. I took the skin of water and attempted, through my nausea, to drink. Once done sputtering and gagging on it, I considered his words again. “How do you know about that?”

“You’ve gone daft. I saw you ride.” Dand sat on his haunches beside where my shield lay. “Is this made out of rowan?”

“Aye. It was a gift.”

“From who?”

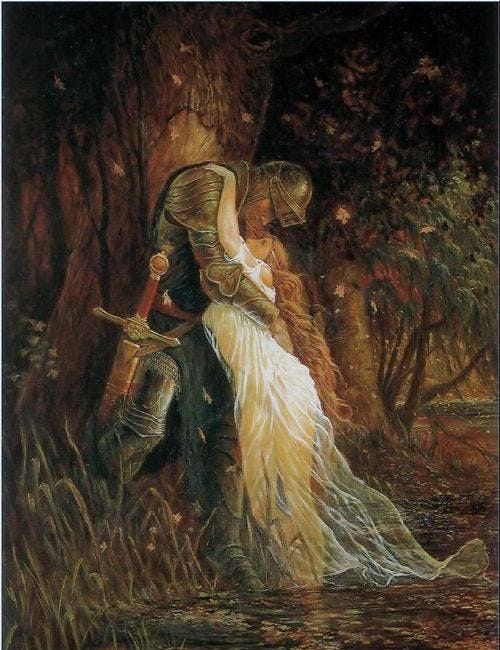

In my mind’s eye I recalled her above me, just as she had been some short nights ago, with her dark hair lose from her plaits. I had been resting near a well, an uncommonly hot night. “She didn’t say.”

“A fairy,” William said with a spit. I didn’t agree with him, but said nothing. In truth, how could I know? She charmed me well enough at the time. “I can smell the fairy magic on it.” He flipped it with a stick and I heard him curse at the sight of the five-pointed star painted in the centre, and I puzzled, trying to remember if I ever saw the star on my shield before. When she gave it to me, I think I was only looking at her. I couldn’t lift my head to see the old man, but I couldn’t imagine him lying about it. That I couldn’t remember what was painted on my own shield proved he must be telling the truth, in my muddy logic. Perhaps she was a fairy after all.

“Allain is a lot of things but I doubt he cavorts with the fair folk,” Brice said.

“If I keep bleeding I’ll be a lot less of things, fair folk or no.” The sky shadowed above as I spoke, a great thick cloud passing over the sun.

It was Brice’s turn to wash himself, splashing his face with a loud shudder. After scrubbing and rinsing his hair he whipped his head, droplets hitting us at the tree but I paid it no mind, though William cursed him. They bickered back and forth, and I fell asleep numbed to the pain of them cleaning me, and I dreamt of her, the dark-haired maid at the well who promised me protection, but why she did so was as much of a mystery as the night’s ride. Seemed her promise broke, and I could only damn myself for my sorry state.

The sound of steel woke me, William examining the damage done to my armour with a furrowed brow. His deep wrinkles might be doing the thinking, the wiseness of the old knight seen in every silver whisker. “Damn shame. Spear?”

I thought about it. Bits and pieces, the light of burning thatch from a nearby farmstead crowded out the gauzy sunlight, the illusion of full-night sky against the brightness of flame. The smell of burning bodies filled me and crowded out all else in my remembering, and despite the distance in time I began coughing. William held my shoulders, and I knew I was still bleeding at the rushed pressure of Brice’s hands. My stomach churned, and I gripped William’s arm for support as I twisted myself to vomit. Nothing came, and I fell asleep again.

Brice’s voice woke me next. “With a rowan shield, no less. We’ll need to get him to a town, find a healer.”

The smell of smoke still filled my head, but I couldn’t move more than a twitch to avoid it. Perhaps I hadn’t travelled as far as I thought. None of the others seemed distressed. They continued to speak over me.

“Where are you camped? Are there no healers?” Dand asked.

William grunted. “Butchers. If you wanted to turn Allain into a ham I’d trust them better. But I can’t think of another plan.”

“Better to be a ham,” I said, low and dry. “Smoked, salted and all. String me up, I might already be hammed."

“I’ll string you up by your goddamn bellend. Can you stand?” William came to my right and tucked a hand under my arm, Brice on the left, and I nodded. Better to move while I died. Tree root in my back or horse under me—I’d rather the horse. They helped me dress, except for the maille, but none of them took up my shield, which I had to mind on my own. We were all superstitious, four fools no worse than the other, so I bore them no ill-temperament for their unwillingness to touch the thing—they had nursed me as much as they could so what was one task for myself? It weighed more than I remembered, but once strapped to my back I was able to climb onto the saddle and Brice and Dand stood on either side of me. Dand gave me worried glances but said nothing, and Brice led the horse on. William donned his helm and we were off, back up the deer path, and the smoke thickened. All the smells of the night before was as brunt as the club to my head.

There is a battle-reek that cannot be known until it is known—a witches’ brew of shed blood, split entrails, horse, metal, leather, churned soil, excrement—I could list more, and try to describe the unnameable things (and some of the benign things, like the flowers in season that one notices before the worst of it) but above whatever I might list, it’s the pervasive sweetness of rot that lends inspiration to void one’s guts. Those flowers in season will forever be tainted by association.

The sun faded with the approach of the wood’s edge. Blotted by cloud or smoke—with the red haze of looming twilight. Had we been so long at the water? But the odour was there, unmistakably. A cold sweat coated my brow, and with the last push of branches, I wavered in the saddle—the road was gone, and only broad sheep fields lay before us, no trees for miles, thick wisping horizon beyond the hoof-tilled soil and lichen-speckled stones. There was a fire in the distance, and a hundred ravens picked at the bloat of horses and men, all prickled with arrows and cracked spearshafts, listing banners still clutched—my spirit dropped into the mud and was stomped as tattered cloth, splintered shield, and whatever else the villagers hadn’t stripped. If I opened my mouth I would taste the air, so I kept it closed, swallowed my worry, and I led the horse forward. He tripped up in the mud and the jostling pained me but I could pay it no mind, we had to find the road, we must have missed the proper route where we had gone down to the water.

The ravens went silent as I turned my mount to keep the forest to my right, as it had been before. It was an ominous silence, and a hundred tiny eyes on my back had my spine wrought with shivers.

But the dead-quiet didn’t last. One gurgled croak and clack of beak at first, then more joined in. Their calls seemed to me an almost human laughter, of grit and chest not natural to birds, and as the noise became deafening and I turned myself to face the field, two hounds barrelled by, yapping and snapping their jaws to cause the birds their flight. I thought I felt a hand at my forearm, but the pressure was odd—I lifted my arm and perched upon it was a hawk, masked as it waited for a hunt.

I lifted the mask and the hawk took flight after the ravens, and the mass of birds all danced in a black whirlwind. The dogs returned to the rear of my horse—who showed an incredible calmness through all the noise and ruckus of animals at his feet, a discipline rarely seen in any horses I had ridden—and with the return of the hawk to my arm, talons around my aketon sleeve, the ravens were laughing again.

“Ah, men! What reason hast thou, to trespass here?” asked the ravens. The hounds ceased their barking.

None of my companions of the morning were with me, and so I had to force my voice. “I’m trying to return home.” It seemed as true as anything else I could have declared to the birds.

“We smell blood on thee. Thou art rich with the blood of other men, and becoming poorer of thine own.”

“That is true. You are wise birds.”

“Wise! The owl is wise. The hare is fleet, and clever. But we know secrets. The water in yon wood, though thou hast made it life-sweet, has not, and will never clean thee.” The cloud of them flitted in and out of bleak shapes until before me stood a figure, an imitation, and it was from that shadow-black face they spoke again: “To brook thy pain will not halt the flow.” The figure pointed ahead of me, and I could see blue crags in the distance. “Seek thee out the mountain hare.”

I couldn’t help but give a meagre laugh. “You speak in riddles.”

“Are not all men riddles?”

“But why must I seek the hare?”

“She will tell of the maid of the mere. Thou must return home, for there is nothing here but to enrich the earth, lest thou take pleasure in carrion as much as we, and now we return to our feast.”

I thanked the ravens and urged my horse on.

***

Away from the field, the sky was right again. Blue and clouded. I never once turned, fearful the ravens might not take kindly to a backwards glance. Magic beasts followed strange rules, and I was in no position, after hearing their riddles, to chance at a curse—if indeed I did see magic and it wasn’t my own madness, which was another possibility that caused my teeth to grind.

My arm weakened and drooped, the hawk flew off, and as I hunched and risked fading into sleep there was a new pressure where the talons had been. William held me with a firm but gentle hand, and hearing footsteps next to my horse again had my head burning. I opened my eyes wider and saw he looked up at me, concern in his brow.

“Where had you gone, William? I thought you left me to stay in the woods, and here you are again.”

“I had never gone,” he said while releasing me, turning to face the path ahead. I managed to straighten and scowl down at him, but I could not read his mind and the four words were his only defence. More steps, on the other side of me, there was Brice and Dand again, and I was dizzy.

Dand walked ahead of me, a hand at his brow to shield the sun. Youthful and spry, there was a bounce to his step as if overeager to run ahead. Brice took the reins from me and my knuckles ached, I had been gripping the leather so tightly. I breathed as deep as my pain allowed me, and returned my hand to the cut. My fingers thawed to the heat of my blood. I looked to each of my companions in turn—none of them made comment about the ravens, or the field of dead, or where they had gone. My mouth tasted bitter with the words of reproach on my tongue but I held it. What would come of my anger? Abandonment would leave me dead faster.

So I swallowed the bitterness and asked instead, “Are we hunting hare?”

“Aye.”

So, they heard the ravens.

***

“If we don’t fix your gut, you won’t make it home, Allain.” Brice sighed, looking down at me. “But if I must carry you, I will.”

I was propped against a fencepost, allowing the horse and myself some rest. Brice and William had helped me from the saddle while Dand found more water, though any attempts to mend me were just as futile as before. My clothes were stiff and crackled with my blood as I moved, I sweat cold, my stomach was sour. I rolled my head against the wood of the post to look at Brice. “Where are we?”

Brice chuckled with an uneasy smile. “Good question. We’ve strayed a bit far from the camp, I think.”

“And I’m starving,” Dand said. “Mountain hare, aye? Over in yon hills?”

“I don’t think you ought to eat her,” Brice said. “If she’s as fae as the ravens, she might take issue with it.”

“I won’t bloody eat her. I’m not stupid.”

“I doubt that.”

I coughed, my eyelids drooped shut. I felt my reality slipping and despite myself a tear shed. “I need you both to go. If William stays with me... you’ll both come back with the hare. Can you fetch her?”

Dand nodded. “Faster than any hounds, and keener of scent, I promise you. We’ll find the mountain hare.”

William stayed behind with me, and we watched them walk off toward the rough hills.

This story is in progress, but I figured since it was getting lengthy I’d split it up. Part Two!

Heavily inspired by the poem La Belle Damme Sans Merci by John Keats and the song Witch of the West-Mer-Lands by Archie Fisher, and the absolutely beautiful cover by Stan Rogers is well worth a listen:

Part 2:

The Well Part 2 - The Rowan Shield

The Rowan Shield She perched at the edge of the well, watching me where I lay under the rim of ancient stone. Leaning forward, she dripped music, black hair merging with the night sky, and what were stars or what were beads of water—her face so pale, where the dark ended she was moonlight, for all I could discern. She had asked if I had waited long, but …

Fabulous- I am a fan of Stan Rogers, as most Canadians are...

This is just extraordinary! I’m enraptured.